Everything You’ve Ever Wanted to Know, and Then Some

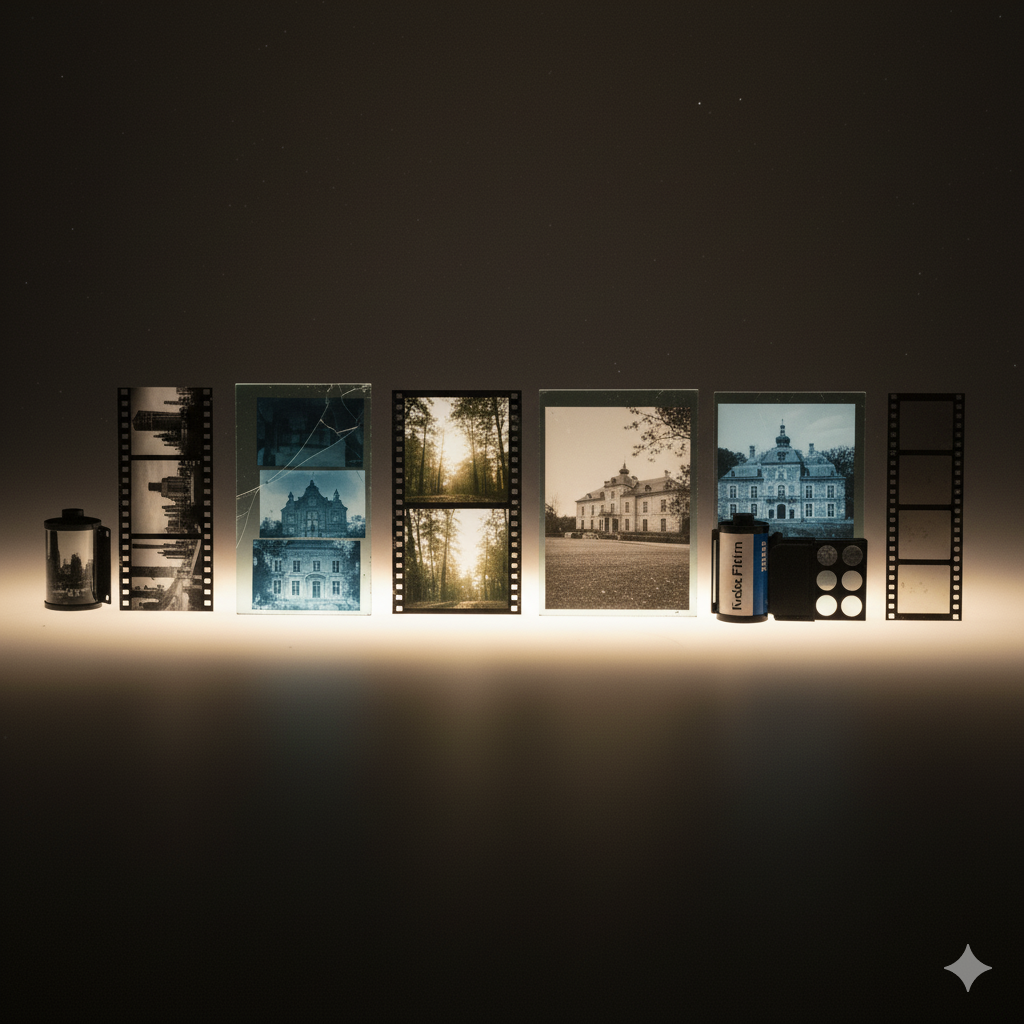

Motion picture film (8mm, Super8, 16mm, 35mm, 70mm) has been around for well over 100 years, but digital film scanning is still relatively new. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was the first movie to be digitally scanned in its entirety for a restoration in 1993. O Brother Where Art Thou? (2000) is considered the first feature film to be scanned and color graded using an entirely digital process. Since motion picture film scanning is young, there are many different types of scanners with varying levels of quality still in use today by companies all over the world. Below, we’ll explain how film scanning works, what to look for in a quality scanner, and why our LaserGraphics scanner is considered the best scanner available today.

Telecine - A Brief History of Film and Television

If you just want to learn about available scanner technology today, jump ahead to the section on resolution.

Before the invention of the television, all movies were shot on celluloid or nitrate based film and projected on film. The entire process was done optically by shining light on or through pieces of film. No part of the image was produced electronically. With the invention of television, we were now able to send moving images electronically and over long distances to anyone with an antenna. However, early video cameras were HUGE, so they were stuck in the studio, and video tape wouldn’t be invented until 1956 with 2” Quaduplex Tape. 2” Quad required machines the size of a large oven or refrigerator in order to play, so it still wasn’t possible to shoot remote, on location video until the Sony Portapack was invented in 1967.

Before 1967, if you wanted to record something outside of the studio for broadcast at a different time, you still needed to record your images on motion picture film. But how did they get the film (an optical format) onto television (an electronic format)? Enter, the “Telecine.”

In its simplest form, the telecine is a film projector pointed at a video camera. This concept is the basis for every single telecine and film scanner that has ever been developed. On the earliest telecines, the film would be played and the video camera would simply record the film. If you ever had film transferred to VHS tape, the film was usually projected onto a screen and a VHS camera was used to record it in real time. However, there was a problem, video and motion picture film have different frame rates. Motion picture sound film is 24 frames per second (fps) progressive and video in North America is 29.97fps interlaced.* Without complex synchronization between the projector and the camera, there could be severe flickering and other visual abnormalities.

To prevent this, a method of capture was created to convert the 24fps film to 29.97fps video. 2:3 Pulldown (also called 3:2) is a method where some of the film frames are duplicated and blended to achieve normal looking motion and fit the frame rate of video. In 2:3 Pulldown, the numbers refer to the number of interlaced video fields each frame of film will receive. In analog video, each frame is composed of two individual “fields” to make one full image. So, although the frame rate is 29.97 full frames of video per second, you’re actually seeing 59.97 half frames of video per second. You can learn more about interlacing here.

The 2 means the first frame of film will be spread onto 2 fields of video, getting one full frame. The 3 means the next frame will be spread over the next three fields of video, giving the second frame of film one full frame of video and one half frame. Every 4 frames of film gets turned into 5 frames of video. If we have a sequence of four frames, A-B-C-D, the pattern of video fields is described as AA-BBB-CC-DDD, or AA-BB-BC-CD-DD where the third video frame is a blend of frames B and C, and the fourth video frame is a blend of C and D.

With digital video, we’re not tied to the electrical grid to establish the timing of our frames, so we can play video at any frame rate we want. Additionally, with modern high refresh display technology like LCD and OLED, we no longer need to interlace our video frames. With contemporary film scanners and TVs, we can capture and display the film at the original frame rate fully progressive, meaning 1 frame of film equals exactly 1 frame of video. Although many people call contemporary film scanners “Telecines” (they’re not wrong), people in the industry prefer to use Telecine exclusively to refer to the original cine to analog tele-vision scanners because of the 2:3 Pulldown. Instead Motion Picture Film Scanner (although a mouthful) or simply Film Scanner, is used to describe the newer, high definition, progressive, frame accurate scanners.

Click here for a full in-depth history of the Telecine.

*In order for broadcast television to work, the camera and your TV have to be perfectly in sync to display the image properly. Since video is an electronic format, the timing comes directly from the electrical grid. In North America, our electricity runs at 60Hz, or the alternating current pulses back and forth 60 times a second. Every two pulses equals one full frame of video, for 30fps. When color TV was invented, there wasn’t enough room in the existing signal standards to send the color information, so the frame rate was slowed down slightly to 29.97fps and the left over space in the signal contained the color information. This change also allowed color TV to be broadcast to existing black and white TVs. In places like Europe, where the electrical system runs at 50Hz, their video frame rates are 25fps. Since these standards were created after the North American NTSC system, they left bandwidth in the signal standard to add color information later. Therefore, European PAL and SECAM both play at exactly 25fps, but NTSC is 29.97fps.

Let’s Talk Resolution

Okay, class dismissed. Let’s get on to some things to look for in a film scanner and what’s available on the market today. One of the most important things is resolution. You’ll want to make sure the resolution of the scanner is high enough to capture all of the original detail in your film. Film is a progressive format (the “p” in 1080p) not an interlaced format (the “i” in 1080i), so you’ll also want to make sure the files you receive will be progressive.

Believe it or not, many of the large national digitizing companies still use old style telecines to convert your film to a digital file (if you skipped the history lesson, go back to learn why this isn’t a good thing). Not only that, but these scanners usually use standard definition cameras! Film is an optical format (as opposed to an electrical or magnetic format like VHS), so the resolution is much higher than what could be displayed on old analog, standard definition, CRT televisions. Before LCDs and HDTV, if you ever wondered why movies looked better in the theatre than in your home on TV, it wasn’t just because the screen was bigger. Your Home TV only had a resolution of about 480 lines of video, or about 640x480 pixels (analog video doesn’t use pixels), but at the theatre they usually projected 35mm and sometimes 70mm film, which have equivalent digital resolutions of as much as 8-12K! Film also doesn’t have pixels, so it can be hard to quantify the resolution, but based on the size of the grain (which makes up the image) and how densely it’s packed, we can estimate a digital resolution.

Film resolutions are dependent on the film stock used and how they were shot. Since film uses grain, not pixels, there are lots of factors that can affect the size and density of the grain.

When looking at scanning services, make sure the scanner they’re using has a resolution that is the same or greater than the rated resolution of your film format. At Scan5, we have a 5K LaserGraphics scanner, which will more than cover the resolution of 8mm, Super8, and 16mm film. This allows us to overscan the film to ensure no content is lost and it's all captured at the highest resolution possible.

Shedding Light on Scanner Technology

The second most important part of a motion picture scanner is the light source. Without it, you wouldn’t be able to see the film! So, maybe it’s even more important than the camera! There are three common types of light sources in use today: Tungsten, White LEDs, and RGB (Red, Green, and Blue) LEDs.

Before the invention of high powered LEDs, tungsten and other incandescent style lamps were used for film projection. These lamps are incredibly bright and have a high CRI (Color Rendition Index), so your film would look bright and vivid when projected onto a screen. However, these lamps are also incredibly HOT. If the projector jammed, any film stuck in the gate would begin to melt almost instantly. When scanning archival film, like your old home movies, it’s important the scanner being used does not use tungsten, xenon, or other kinds of incandescent hot lamps. Many of the old telecine style scanners use off the shelf film projectors which use tungsten lamps. So unless the company using them has modified the projectors, you risk permanent damage to your film by using these types of scanners.

LEDs are a much safer alternative to tungsten. They use much less energy and can produce more light, so they stay relatively cool during operation and there’s no risk of melting your film. The problem with LEDs, however, is they usually have a lower CRI. To circumvent this, the higher end scanners, like our LaserGraphics, use a full RGB light source to properly reproduce every color of the rainbow. On budget scanners, like the MovieStuff RetroScan series, they only use white LEDs, which greatly limits the color rendition of the scans. Another added benefit of an RGB light source is that you can control the color of the light to color correct the film in the scan without digitally processing the image. On white LED scanners, all color correction has to be done digitally, whether by manipulating how the camera interprets the color or by changing the color in video editing software.

High Dynamic Range (HDR) refers to how many unique light levels from pure black to pure white a scanner can capture or that a display can show. Standard Dynamic Range (SDR) tends to be more contrasty with dark blacks, little detail, and bright, sometimes blown out highlights. HDR has more detail in the shadows and can better preserve highlight detail than SDR, which makes images look more true to life. Motion picture film, especially negative film, has a much wider dynamic range than most analog and digital video cameras. In order to capture all of the original detail and dynamic range of the film our LaserGraphics can scan the film in HDR by taking two pictures of each frame, one to preserve shadow detail, and one to preserve highlight detail, and then blend them together to give you a vivid HDR final image. Most motion picture scanners only take one picture of each frame at a single set exposure, which limits the dynamic range of the scan.

Transport - How the Film Moves Through The Scanner

Sprocket Drive

A single reel of film can contain thousands of feet of feet. How do you move all of that film through the scanner carefully? If you look on the edges of your film, you’ll see a series of holes called Film Performations or Sprocket Holes. These holes are used by projectors and cameras to advance the film. Gears with small teeth engage with the sprocket holes and move the film forward. When the film enters the gate (the part of the camera where the film gets exposed, and the part of the projector where the film is illuminated) it needs to stop for 1/48 of a second so the frame can be exposed or projected. A pin is inserted into one or more of the sprocket holes to keep the film steady during this time. Then, the shutter covers the film, the pin is removed, and a claw enters one of the sprocket holes and pulls the frame down to the next frame. It works a lot like a sewing machine, in fact, one of the first motion picture cameras was developed by The Lumiere Brothers, who owned a sewing machine factory.

Because of all these pins, claws, and sprockets, there is a high risk of damage to the film if the camera or projector is threaded incorrectly. If the film becomes misaligned or the projector jams, the sprocket holes can be torn or the image can receive punctures; permanently damaging the film. If the damage is severe, the film can’t ever be projected again.

Many motion picture scanners use the same kind of transport to move the film through the scanner, especially the older style telecines still in use today, which use off the shelf projectors. Although sprocket drives and pin registration offers a stable scan, they’re not safe for archival film (like home movies) due to the risk of permanent damage. Old films are prone to shrinkage, which can prevent the sprocket holes from properly aligning with the sprockets, claw, and registration pin. That is why all one of a kind archival films should always be scanned using a sprocketless scanner like our LaserGraphics.

Laser Guided

Since sprocketless scanners use continuous motion, meaning the film doesn’t stop in the gate momentarily to be captured, the scanner needs to know when to take the picture. Most sprocketless scanners like the Film Fabriek HDS+ and the RetroScan use lasers to monitor the sprocket holes and use them to trigger the scans. These work well enough, however, if the lasers are misaligned, the film is clear, sprocket holes are damaged, or the film is particularly warped, the laser might not trigger and your video file will be missing frames.

Optical Pin Registration

Our LaserGraphics scanner uses optical pin registration to trigger the scans and stabilize your film. As the film passes through the gate, the scanner analyzes the film to recognize and align each individual frame during the scan. Since the Film Fabriek and RetroScan use a laser for the trigger, there is no stabilization done during the scan. That means the film can move slightly side to side and due to the small imperfections in each sprocket hole, frames can be triggered a little early or a little late causing vertical instability as well. On these scanners, additional stabilization software needs to process your scans to create a steady image, this can potentially generate artifacts in your resulting file. Our LaserGraphics does all of the stabilization in the scan before the file gets saved, so there is no additional processing. You will receive the files directly from the scanner with no alterations.

Capstan Drive

Our LaserGraphics is also “capstan” driven to provide a perfectly steady and gentle movement through the machine. Since the capstan is what drives the film, the overall tension on the film can be reduced, preserving its longevity. Some of the lower end scanners like the RetroScan are completely driven by the take-up reel. On these style scanners, a lot more tension is required to move the film through all of the rollers and the gate.

Smart vs Dumb Scanning

Lastly, most film scanners are “dumb.” They don’t know where the film is or what it’s doing. They’re either on or they’re off. That means if your film breaks during a scan, the scanner has no idea and it’s going to keep spinning all of the reels and capstans. Usually, this isn’t much of a problem, however, since the machine continues to move, any loose film can now get caught, tangled, scratched, or otherwise permanently damaged while the operator races to stop the machine. Not only does our LaserGraphics scanner know exactly where the film is at all times (it scans thumbnails of each frame and assigns a timecode) it has automatic failed splice detection. So if an old splice fails during scanning, the scanner immediately stops! We can then repair the splice and rethread the scanner, at which point, the scanner will detect the last scanned frame and automatically continue scanning where it left off. On other “dumb” scanners, two video files would need to be created and edited together, or the scan would need to be restarted from the beginning.

Final Thoughts and Things to Avoid

Previewing Film - Why We Don’t Recommend It, And How To Do It Safely

We understand that film scanning is an expensive endeavor, so there’s a desire to preview your film prior to transfer, to make sure it’s something you actually want. However, every time you handle the film, you put wear and tear on it, and especially if you’re inexperienced you risk permanent damage. Our technicians have over two decades of film handling experience, so you can rest assured that your film will be handled with care. To stay as archival as possible, the next time you handle your film, it should be the last time; by getting it digitized. The digital file will never change, and you can watch it as many times as you want without risk of deterioration.

In our experience, almost all home movie archives have interesting and valuable content. Shooting film was expensive, so people took the time to learn how to use their cameras and were selective about what they filmed. The film was almost always viewed by a family member some time in the past, and if the film didn’t turn out, they threw it away. If your film has been spliced onto reels larger than 3in, that means someone took the time to edit multiple reels together, which means someone reviewed the film and removed any bad clips.

If you must preview your film before you bring it to us, do not play the film in a projector! Due to the sprockets and claws mentioned above, there is an increased risk of permanent damage. If your film has shrunken at all, it will jam in the projector and the damage may prevent the film from being scanned. The projector may also require repairs or calibration to function correctly. The safest way to preview film prior to scanning is to acquire a table top viewer for your specific format 8mm, Super8, or 16mm. These have minimal moving parts and are operated by hand, so if you encounter any problems or a jam, you can stop the film immediately to reduce any damage to the film. You can identify the type of film you have by inspecting the sprocket holes.

Why We Can’t Preview Film For You

As much as we would like to preview film for you, in order to load the film into our scanner for review, we have to prepare the entire reel for safe handling and transfer, regardless of how much film you would like to see. This includes splicing new leader onto the head and tail of each reel for protection and safe handling, removing the film from old reels, inspecting the film for damage and making any repairs, and fixing any broken splices. The labor involved in preparing the film is where most of the expense comes from. We can’t put any film in our scanner without inspecting and preparing it first. This is the only way we can ensure your film won’t get damaged during the scanning process. If we determine during the inspection that we can’t transfer any of your films due to degradation, there will be no charge for those reels. You only get charged for the film that actually goes through the scanner.

Storage and Preparation

Make sure your film is stored in a cool dry place. Attics get incredibly hot and humid in the summer which greatly accelerates the deterioration of the film. Basements are better, but they tend to get very humid. If the film must be stored in a basement, ensure the environment is climate controlled and there is a dehumidifier present.

Film needs to breathe! As the film ages, the chemicals that make-up the emulsion and base slowly let off gasses. If these gases don’t have any way to escape, they will begin to slowly eat away at the film. Eventually, the film will begin to smell like vinegar. This is aptly named Vinegar Syndrome, and once this process starts, it cannot be stopped. But don’t despair! The process can be slowed down dramatically, and unless the film has become brittle or fused, we can still transfer your films! If your film is fused and too brittle to transfer, we recommend sending the film to TeamWork Media in Canada.

If your film is in old metal cans, remove them immediately. The best way to protect your film is to place the reels in vented plastic archival storage containers. When we transfer your film, we will also remove the film from the original metal reels and return it on archival plastic reels or cores for safe long term storage. Store the film in a breathable container. Archives use corrugated cardboard because it is breathable and won’t leech any chemicals back into the film. You can find all sorts of archival storage containers at Gaylord Archival. Although not necessarily archival, Banker’s Boxes are a great storage alternative. If you must use plastic storage bins, drill some holes near the top to allow any gases to be vented out. If films are stored in a basement, make sure they’re off the ground in case of water intrusion or flooding.

Start Your Order Today!

Now that you know everything there is to know about film scanning, you’re ready to get started! Visit Scan5.com to begin your order. Film has a much longer shelf life than video tapes, so if you have a lot of film, you can do it in smaller batches to spread out the cost. If you find any reels that smell of vinegar, as mentioned above, definitely prioritize those films first! Those films will continue to degrade more rapidly than the others.

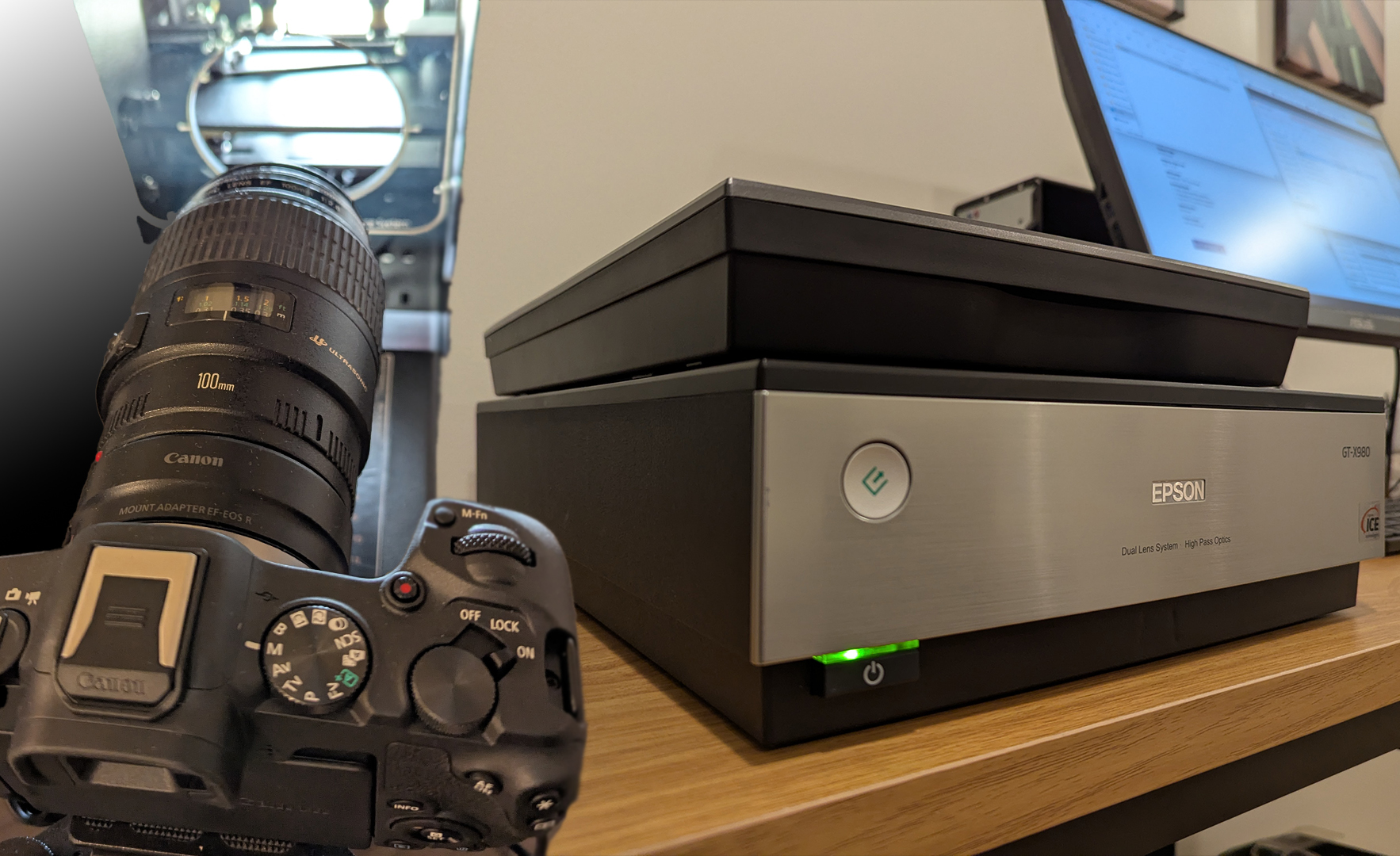

I hope we’ve shown that Scan5 is THE place in Chicago to get your film digitized. We have a state of the art LaserGraphics scanner and knowledgeable staff that still shoots on film to this day! If you’re looking at other companies, make sure they use a sprocketless scanner and are scanning in High Definition to preserve all of the original detail in your film. Scan5’s LaserGraphics scanner can scan up to 5K depending on the format and uses a High Dynamic Range light source to ensure nothing is missed and all of the original detail will be present in your digital file. We can provide high quality MP4s for easy viewing, lossless ProRes files, and more! Just ask! Scans can also be provided cropped (frame lines and sprocket holes removed) or overscanned (sometimes there’s extra information outside the original frame).

Click here to start your order where you can schedule an appointment, receive a prepared UPS shipping label, or arrange a courier pick-up (free for orders of a certain size in the Chicagoland area). You can also contact us here, we’d love to hear about your film!